Feel good your way: Insight summary 2 - Supporting young people's mental health

Feel good your way

Contents

- Introduction

- The State of Young People’s Mental Health

- Protective Factors for Positive Mental Health

- Support for Mental Health

- The Role of Physical Activity in Supporting Mental Health

- Guidance on using Physical Activity to Support Mental Health

- Implications for Campaign

1. Introduction

The purpose of this summary is to draw on existing research since 2017 and create a broad insight into the lives of young people. Whilst this is not a systematic review, it offers a broad picture of young people’s current experiences.

Where available evidence allows, we focus particularly on our audience of interest of girls aged 11-15 in Greater Manchester. The insight from this summary, along with that from our other summaries in this series, engagement with stakeholders, and direct engagement with young people, will inform the creative brief for the Greater Manchester Moving campaign.

As we have seen in the first of our insight summaries Young People’s Lives, young people are facing increasing complexity and challenges in their lives, particularly in light of the Covid-19 pandemic and the current cost of living crisis. In this insight summary we will explore available evidence around the state of young people’s mental health.

We will draw on existing research to present a broad view of the current support available to help young people with their mental health. This includes the role that physical activity can play.

2. The State of Young People’s Mental Health

The picture for young people’s mental health across the UK at present is bleak. A crisis was already looming prior to the Covid-19 pandemic, however, the last two and a half years have significantly exacerbated the challenges.

Data from NHS Digital (2021) showed that, in 2021:

- One in six young people, age 6-16, had a diagnosable mental health disorder, up from one in nine in 2017 (although at least now holding stable since 2020).

- 39% experienced a deterioration in mental health since 2017 (c.f. 22% experiencing an improvement).

- 38% 11-16-year-olds had trouble with sleep and this was worse for those with a probable mental health disorder.

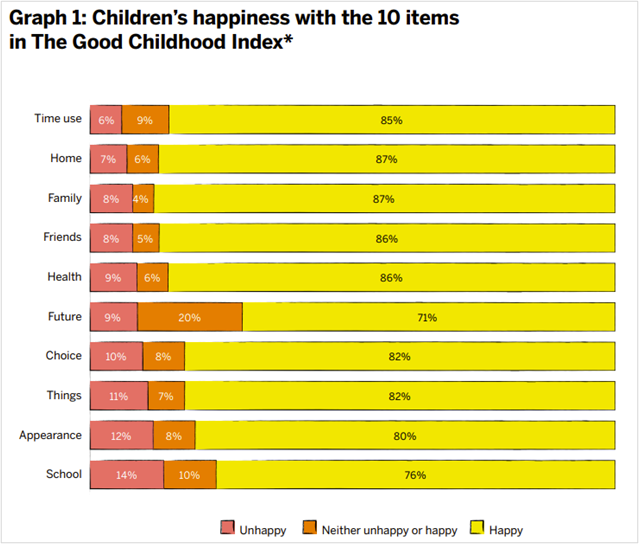

Key findings from the latest Good Child Report (2022) painted a similar picture:

- UK children’s happiness with their lives continues to decline. One in nine children deemed to have low wellbeing, one in 16 unhappy with their lives overall.

- More children (10-15) are unhappy with their appearance than with family, friends, school and schoolwork (one in eight). Girls are more likely (18%) to feel this way than boys (10%).

- Happiness with school and schoolwork declines significantly with age, and was significantly lower among children in lower income households.

- 17% children (10-17) said they did not cope with changes due to Coronavirus.

- Over half of parents and carers feel that the pandemic has had a negative impact on the education of their children.

- 85% of parents and carers are concerned about the impact of the cost of living crisis on their household/family over the next 12 months, which will only get worse as this crisis unfolds.

A report from MIND (2021) found that, in spring 2021:

- 68% young people (13-24) said their mental health was worse since first lockdown (51% much worse).

- A third (32%) of young people who struggle with their mental health have self-harmed to cope, making them more than twice as likely to have coped by self-harming than adults (14%).

- Over three quarters of young people (78%) have been over or under-eating to cope with the pandemic.

- Top coping mechanisms for YP were:

- Sleeping too much or too little (77%).

- Spending time outside (75%).

- Reading, watching TV/film or listening to music/radio (75%).

- Spending too much time on social media (73%).

- Eating too much or too little (72%).

- Exercising (57%)

- Loneliness hit young people’s mental health hardest – nearly nine in ten (88%) young people said it made their mental health worse.

- Young people are also more likely to have been negatively affected by lack of private space in their house (56% said it affected their mental health, in comparison to 36% of adults).

- On the flip side, some young people (18%) said their mental health had got better since the first national lockdown. Some said that the pandemic had made it easier to talk about their mental health, as more people acknowledged its impact on wellbeing. 74% said the pandemic had changed the way they think about mental health.

Analysis of the Understanding Society Covid-19 survey data (July 2020-March 2021) found that girls’ mental wellbeing (11-15) had declined more than boys’ (Mendolia et al, 2022). They saw greater increases in emotional and behavioural difficulties, greater overall life dissatisfaction (including specifically greater dissatisfaction with school, friends and appearance). This was worse still for girls from lower-income families.

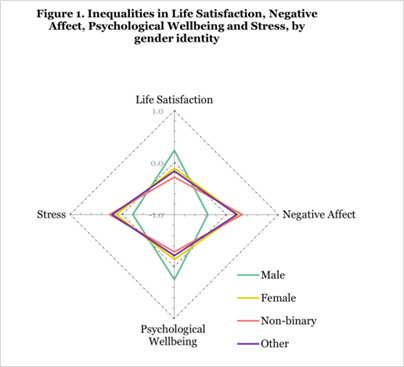

Similar findings in the BeeWell survey (2022) show that, in Greater Manchester, girls and those identifying as non-binary scored worse than boys on all wellbeing dimensions studied – lower life satisfaction and psychological wellbeing, higher stress and negative effect. N.B. The same was true for those identifying with a sexual orientation other than heterosexual.

The report also revealed:

- 16% of young people experiencing high level of emotional difficulty.

- 40% of young people don't get enough sleep (45% girls).

Findings from the 2022 BeeWell survey (BeeWell, 2023) revealed that figures have remained largely consistent across the two years.

This including observed inequalities, particularly by gender and sexual orientation (see chart).

The survey also included a longitudinal element, which showed a decline in wellbeing from Year 8 to Year 9. This is in line with other studies which demonstrate that wellbeing declines with age during adolescence.

The Education Policy Institute (2022) undertook further analysis of the BeeWell 2021 data and made a series of recommendations as to what the government should prioritise, including:

- Ensuring that young people feel safe and have a sense of belonging in their communities.

- Ensuring equity of access to community resources.

- Ensuring opportunities for physical activity exist in all areas.

Whilst a campaign cannot necessarily make a place safer or create new opportunities, it can serve to highlight where opportunities exist and to support providers to address these issues wherever possible.

Supporting young people’s mental health is a challenge that schools are really struggling with too. A further report from MIND (2021) looked at support for mental health in secondary schools in England and found that:

- 96% of those surveyed reported mental health affected schoolwork some or all of the time.

- 69% of those receiving Free School Meals (FSM) say ‘all of the time’ (c.f. 54% not FSM).

- Seven out of ten reported absence from school due to mental health. Where parents reported reason for absence as mental health, less than a third of schools approved as an authorised absence. Some schools even threatened parents with punitive measures for absence due to mental health.

- Almost half of YP who had a mental health issue that impacted behaviour were disciplined for it (49% girls, 41% boys).

- 78% said school made their mental health worse.

We know that, as a consistent trend:

- Girls’ mental health is worse than boys’.

- Half of mental health conditions become established before the age of 14.

- Girls are currently less likely than boys to do enough physical activity to benefit their wellbeing.

- Girls are more likely to drop out of sport and physical activity altogether during this age.

3. Protective Factors for Positive Mental Health

Our understanding of mental health has expanded massively in the last 30 years (NICE, 2022), with mental health only now starting to be seen as of equal importance to physical health in our overall health and wellbeing. There are now a wide range of excellent sources of guidance as to what can support better mental health. Here we have selected a few that present a variety of perspectives.

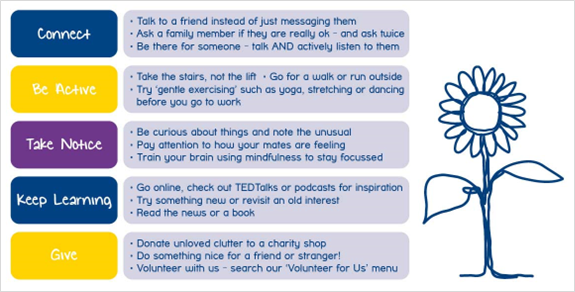

Perhaps one of the simplest and most widely used approaches is the Five Ways to Wellbeing. Originally designed by the New Economics Foundation (2011), it is now used widely by national mental health charity Mind, the NHS, and public health teams within local authorities. The approach presents five evidence-based factors which support better mental health: Connect, Be Active, Take Notice, Keep Learning and Give.

MIND, amongst others, offer a range of online advice for how individuals can build these principles into their own lives, although it is widely acknowledged that some of the factors are easier to achieve for different people, depending on both personal and wider system related factors.

More recently the Mental Health Foundation undertook a number of reviews of the current literature (Kousoulis et al, 2021) around what works to support positive mental health. Identified approaches were reviewed by both academic experts and members of the public who experience, or supported someone who experiences, mental health challenges. This process identified 11 key protective factors (Mental Health Foundation, 2022).

- Get closer to nature

- Learn to understand and manage your feelings

- Talk to someone you trust for support

- Be aware of using drugs and/or alcohol to cope with difficult feelings

- Try to make the most of your money and get help with problem debts

- Get more from your sleep

- Be kind and help create a better world

- Keep moving

- Eat healthy food

- Be curious and open-minded to new experiences

- Plan things to look forward to

The Mental Health Foundation also worked with various partners to produce mental health support resources, such as this toolkit with information, advice, and exercises, produced in partnership with Wolverhampton Wanderers FC.

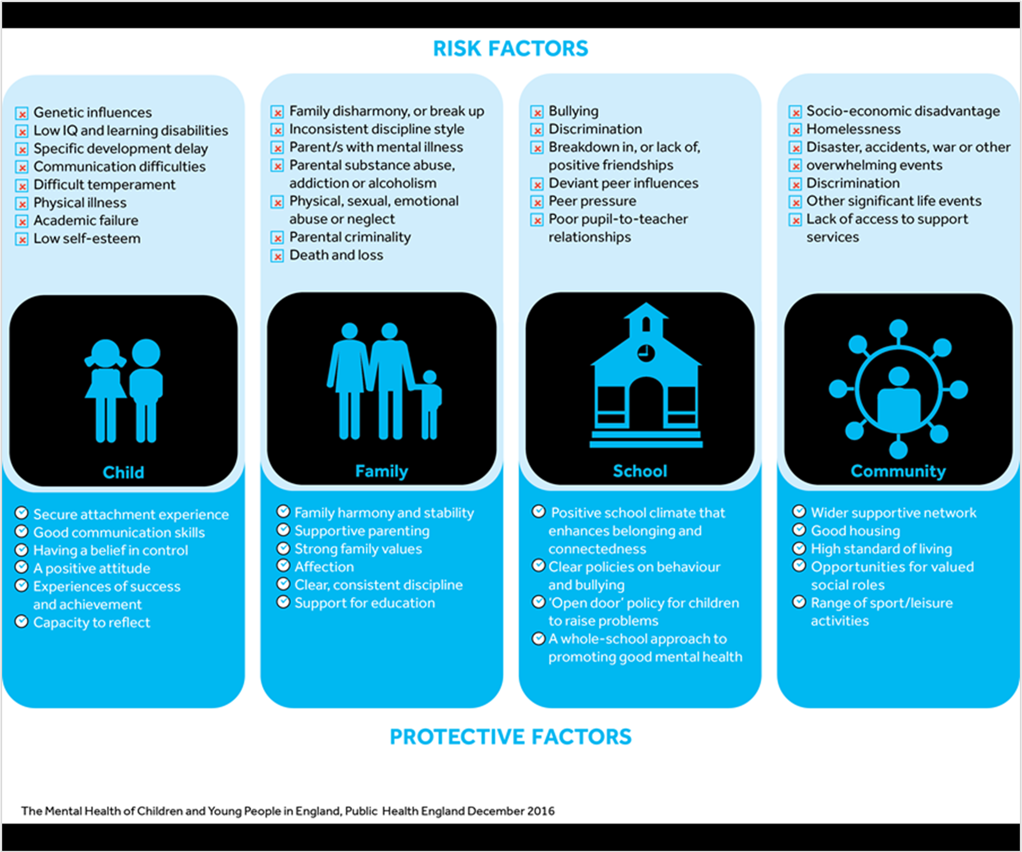

The Anna Freud National Centre for Children and Families offer a wide range of support for schools, parents and carers. They promote the framework (below) from Public Health England of risk and protective factors around mental health. They talk about mental health as a spectrum, as opposed to something binary, and discuss the importance of resilience in children and young people, to enable them to cope when they face difficulties in life.

Another useful framework is the Mental Wellbeing Impact Assessment framework which is used by both Health Protection England and Public Health Wales (National MWIA Collaborative, 2011). It supports examination of mental health across four protective factor domains:

- Enhancing a sense of control

- Increasing resilience and community assets

- Facilitating participation

- Inclusion

These are set against the influence context of individual characteristics and the wider social determinants of health, such as where you live and the opportunities available to you.

The aim of the framework is to enable the assessment and improvement of policies, programmes or services to ensure maximum benefit to people’s mental health. The approach has parallels with Health Impact Assessments which are widely used in Local Government, but with a specific focus on mental health.

We also know that loneliness is a big issue for young people, particularly since the pandemic, when repeated lockdowns left young people detached from many of their social connections and support networks and missing out on many of the character forming opportunities and experiences that they would normally encounter.

Research from the What Works Centre for Wellbeing (Marquez, 2022) found that females, and LGBTQIA+ young people were more likely to experience loneliness. Community characteristics were also associated with loneliness, with loneliness lower in areas with higher perceived neighbourhood quality and sense of belonging to where they live. These acted as protective factors for those with individual risk factors for loneliness, meaning young people in those areas were less likely to be lonely in spite of other challenges.

Throughout all of these examples, being connected, social acceptance and social support are frequently highlighted as key to positive mental health. These are all strong contributors to young people feeling a sense of belonging and being content with who they are and where they are in life.

4. Support for Young People’s Mental Health

Getting support for mental health issues

Most best practice now promotes the treatment of mental health conditions at home and in the community, alongside a multi-agency approach which ensure that the contributory factors to poor mental health can be addressed, not just the symptoms. Nonetheless, after over a decade of austerity, followed by a global pandemic, and now a cost of living crisis, public services are stretched in every domain, meaning the care people receive is not always able to match the aspiration.

A systematic review of studies about accessing mental health support (2021) found four common barrier/facilitators to young people accessing mental health support:

- The most prominent barriers to accessing help were a lack of knowledge about available support and services.

- The perceived social stigma and embarrassment associated with having mental health issues.

- The third factor related to the importance of trust and confidentiality between the YP and whoever was involved in providing support.

The fourth theme was around structural barriers, such as cost, logistical barriers, or availability of appointments.

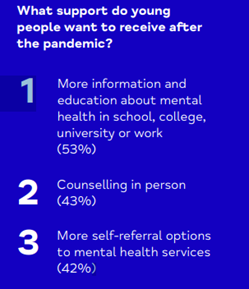

According to a report from MIND (2021), even when someone is ready to ask for support, accessing it in the current climate is far from straightforward:

- 28% of all people who tried to access support were not able to do so.

- 42% of young people who accessed mental health services had to wait three months or more.

- 15% of young people didn't ask for support as they felt their situation was 'not serious enough' – citing that they thought others were worse off, they didn’t want to burden the NHS in a time or crisis, or that they believed everyone's mental health was bad due to the pandemic.

- Many young people said they simply didn't know where to ask for support – especially when schools were closed: “Going through my education institution to get mental health support has been more beneficial for me. It should be on the school curriculum, as it can be difficult to tell if you’re struggling, there’s not enough awareness of what that looks like.”

- Where support was available, young people preferred face to face counselling (43%) to online/phone (17%).

65% young people thought they would have to support others more with their mental once restrictions eased: “I feel there might be a social expectation after easing to be always doing things and always be in groups and doing things. Like I know people are saying at school that everyone’s gonna go to London every weekend in the summer, and it will make people socially stressed and overloaded.”

We also know from Mind’s Making the Grade Report (2021), that schools are currently struggling to respond to the crisis in young people’s mental health too. In response, Mind are running the Fund the Hubs campaign. Calling for the government to support a network of youth early support hubs for 11-25 year olds around the country.

Support available in Greater Manchester

In Greater Manchester, in 2018, only 33.5% children and young people with a diagnosable mental health condition were able to be seen by an NHS-funded mental health service. The city has been working hard to improve things and, following a £74 million investment in services, that rate was up to 45% in early 2021. A marked improvement and above the national average of 41.2%, but still a long way to go (GMCA, 2021).

The BeeWell Project has also sparked a range of other co-creation initiatives, in addition to the planned campaign, which are seeing young people engaged to help design their own solutions to this crisis (GMCA, 2022).

The most common NHS route for supporting young people’s mental health is through Children and Young People’s Mental Health Service (CAMHS (You may also see this referred to as Children and Young People’s Mental Health Services (CYPMHS)), which can be accessed via a referral from a GP. Support covers a range of conditions, including depression, problems with food and eating, self-harm, abuse, violence or anger, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia and anxiety, among other difficulties. Within Greater Manchester, each local authority has its own CAMHS team and Young Minds have some helpful guidance for young people on what CAMHS is, what happens when someone is referred to CAMHS, and what happens next.

Nationally, a number of charities offer free online resources to support young people’s mental health. Some examples are:

- Mind offer a range of online resources for YP age 11-18, which cover self-help, supporting a friend with their mental health, and advice for parents or carers. They also added additional resources to help support people through the challenges of the pandemic. Information for young people on mental health and wellbeing.

- Young Minds are a youth focused charity who have support and guidance for young people and their supporters.

- Campaign Against Living Miserably (CALM) have a wide range of guides on different topics from body image and bullying to self-harm and suicide.

There are also a range of mental health charities in Greater Manchester:

- 42nd Street offer a wide range of early support, counselling, therapies, group and online support.

- Manchester Mind offer a range of free online and face to face support and counselling services targeted for children and young people. They also have an additional online self-care hub with tips and advice for young people.

- There are freephone crisis lines for each GM borough.

- Online services are available from Shout (All Ages) and Kooth (11-18 focused).

- Place2Be offer support in schools Improving children’s mental health in schools – Place2Be.

- In addition, Youth Focus NW partner with 42nd Street to support young people to have a voice in mental health services across Greater Manchester.

Resources for parents, teachers and supporters

- Anna Freud National Centre for Children and Families has a ‘Mentally Healthy Schools’ Resource Library with hundreds of documents with information, guidance, ideas for lessons or assemblies, training opportunities and reports about supporting young people’s mental health in schools.

- Young Minds have specific resources for parents and for supporters.

- Campaign Against Living Miserably (CALM) have advice and guidance if you’re worried about someone else.

- Dove have a range of online resources for parents, teachers and youth leaders around girls’ self-esteem, aligned to their ongoing Self-Esteem project.

5. The Role of Physical Activity in Supporting Mental Health

We saw in Section 2 that being active frequently comes up in guidance and best practice as a valuable tool to support better mental health. Not only that, there are also a range of other common factors, such as social support, spending time in nature, better sleep, and learning and experiencing new things, which being active can help to facilitate.

In fact, there is now widespread evidence that being physically active is good for mental health. According to the World Health Organisation (2022) there is a strong evidence base to suggest that for adults, regular physical activity reduces symptoms of anxiety and depression, improves cognitive health, and supports better sleep. For children and young people, the evidence base is less well developed, however evidence to date suggests that physical activity supports improved cognitive functioning and reduces symptoms of depression.

A 2017 study (Wu et al) also found that, for adolescents, playing a team sport has positive benefits for life satisfaction. One of the authors, Dr Chia-Huei Wu, Assistant Professor of Management at LSE, said:

"When competing and succeeding in sport, this study shows that the social environment of the team is important in terms of overall life-satisfaction. We found that this can be explained by the social interaction and feelings of identity that comes from being a team-member, which are not as present when an athlete pursues their own individual goals."

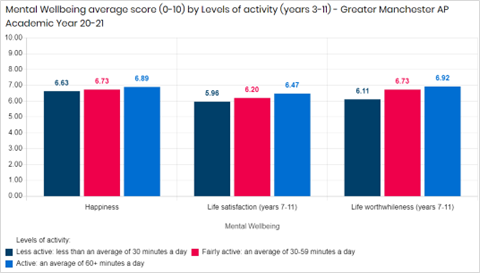

From Active Lives survey data (Sport England, 2021) we can see there was a general decline in life satisfaction for children and young people in Greater Manchester since before the pandemic, however those who are meeting CMO guidelines consistently score higher when compared with young people who are less active (6.47 v 5.96). Scores are also higher for seeing life as worthwhile (6.92 v 6.11) and happiness (6.89 v 6.63). All on a scale of 1-10.

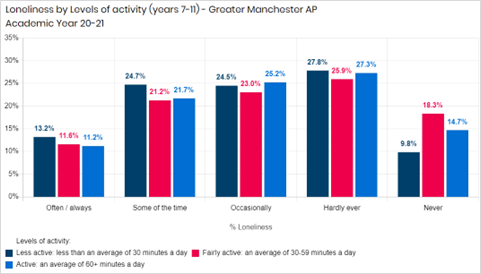

Those who are active are also less likely to say they are ‘often’ or ‘always’ lonely (11.2% v 13.2%) or lonely ‘some of the time’ (21.7% v 24.7%) than those who are less active.

Awareness of physical activity guidelines and benefits to mental health

Despite these benefits, research from Britain Thinks (2019) found poor awareness of the guidelines for children and young people.

In their PE & School Sport Survey report (2022) Youth Sport Trust also highlighted that only 42% parents of under 18s were aware that children 5-18 should be doing 60 mins of physical activity per day, although 75% recognise the benefits to physical health and 74% to mental wellbeing. 77% are also concerned that children are not getting enough physical activity.

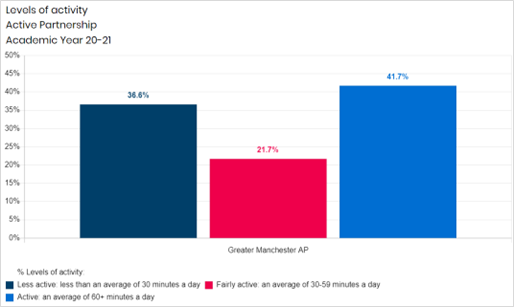

Women in Sport (2022) found that young people themselves recognise the benefits too, with 93% of girls and 94% of boys saying they knew the benefits. 76% girls and 77% boys also said they wanted to be more active, but as we saw in our first insight summary, many are still not achieving necessary levels. According to Active Lives (Academic Year 20/21) only 41.7% young people (5-16) in Greater Manchester are engaging in the recommended amount of physical activity to benefit health (36.6% do less than 30 mins/day).

Those who took part in the BeeWell Survey (2022) were also found to be missing out, with only a third doing 60 mins per day.

There are a multitude of complex reasons for this which are captured in our first insight summary, Young People’s Lives.

They include, but not exclusively, the fact that, whilst young people may recognise the functional health benefits, they do not necessarily identify with the more immediate benefits, such as enjoyment, boosting confidence, or social support. This mean they do not see being active as attractive or worthwhile in the moment, but instead it becomes something they should do.

6. Guidance on using Physical Activity to Support Mental Health

Whilst we have seen that the benefits of physical activity for mental health are increasingly well established, they are certainly far from a given. The experience is crucial to whether physical activity is a risk or protective factor.

Negative experiences of being active and of active environments can be detrimental to mental health, for example where young people feel it’s too competitive, too serious, not enjoyable, or where they have felt excluded or not good enough. The right environment and experience however can create:

- Sense of belonging, feeling part of something.

- Social support.

- Sense of achievement.

In turn, this impacts things like life satisfaction, sense of purpose, feeling valued and ability to cope. How an activity, opportunity, or intervention is delivered is therefore of the upmost importance.

In 2022, the Sport for Development Coalition published a policy brief and research report: Moving for Mental Health: How physical activity, sport and sport for development can transform lives after COVID-19. Together they identified policy recommendations on how to leverage the mental health benefits of physical activity for public good, alongside key components of a successful programme or opportunity. The report emphasised:

- Social support from a trusted source, including peer support

- Trusted and supportive adults, especially coaches, who are comfortable and able to discuss mental health

- A suitable mechanism by which to address mental challenges or concerns and build resilience.

The report also highlighted a lack of knowledge amongst healthcare professionals to offer suitable advice and support for young people experiencing mental health challenges in relation to physical activity. In addition, there is a lack of funding to support community physical activity as part of standard mental health treatment pathways.

A subsequent report from Sported (2022) described a model of good practice for physical activity sessions intended to promote positive mental health for young people. The report advocated:

- Consideration of how implicit and explicit forms of mental health support can be used, recognising that both are of value, either singularly or combined.

- Identify specific needs within a group in advance and continue to monitor activities to ensure they adapt to new issues.

- Ensure sessions are of a size that promotes interactivity among participants and allows them to feel comfortable in contributing.

- Empower young people to contribute to support structures through defined roles or processes that incorporate and recognise their contributions.

- Involve third-party service providers where specific expertise, extra capacity, or a new perspective is helpful.

- Frame mental health support in the language and lived experience of participants and their community.

Give participants time to acclimatise to activities and conversations around mental health.

Women in Sport (2022) advocate eight principles for creating meaningful and enjoyable physical activity experiences for girls. Whilst these are not specific to supporting mental health, they are key to creating welcoming and inclusive environments where girls can feel a sense of belonging.

Other inclusion guidance which may be useful to reference are:

- Activity Alliance Inclusive Communications Guide

- Stonewall Rainbow Laces Lesson Packs for schools and colleges

Whilst not a programme or opportunity in itself, our campaign should take into account these factors in the way that physical activity is presented.

Additionally, Mind (2018) have a toolkit for sport and physical activity providers wanting to support mental health through their activities, which is more focused on the benefits to organisations and the safeguarding requirements.

There are also a number of online guides for young people who want to engage with physical activity themselves in order to benefit their own mental health, for example:

- Mind: Tips for young people to become active, as one of the Five Ways to Wellbeing.

- Mental Health Foundation: Guide to looking after your mental health using exercise.

7. Implications for Feel good your way

- Young people’s mental health is in crisis, with girls mental health even worse than boys.

- Physical activity has a clear role to play in supporting young people’s mental health.

- Whilst young people do recognise the long-term benefits of physical activity for health, they do not always see the immediate rewards, so the campaign needs to display these at every opportunity.

- Language will be key and should reflect that used by our audience in day to day life as opposed to medical or academic terminology.

- Mental health difficulties can be wide ranging, both in terms of who they affect and how they are affected. We should therefore be careful not to generalise or make assumptions about what young people experiencing these challenges might be thinking or feeling.

- Physical activity not only has benefits for mental health in its own right, but it is one of several protective factors which can be presented in combination with other beneficial opportunities such as connecting with nature, connecting with others, social support and learning something new.

- Physical activity can be a risk as well as a protective factor for mental health depending on how it makes a young person feel. The campaign should therefore focus on presenting sport and physical activity as an inclusive and welcoming space and not one filled with competition, judgement and the possibility of failure.

- Giving young people a sense of ownership and a sense of belonging will help to reduce feelings of anxiety and boost a range of wellbeing measures.

- Mental health support services are struggling to keep up with current demand, meaning that even small differences to young people’s mental health could offer welcome relief, particularly for those who may be waiting for professional support.

- School has been a challenging environment for many young people in recent years, so presenting physical activity as a positive, safe environment which is separate to school, and in particular separate to PE, is likely to be well received.

NB. This insight report was produced by Proper Active as part of the Feel Good Your Way campaign.

8. References

- BeeWell (2022) BeeWell Survey 2021 Headline Findings

- BeeWell (2022) Evidence Briefing 1: Inequalities in Young People’s Wellbeing Centre for Mental Health (2020) COVID and the nations mental health

- Britain Thinks (2019) Understanding Inactivity in Greater Manchester

- Education Policy Institute (2022) Neighbourhood Characteristics and young people's wellbeing in Greater Manchester

- GMCA (2021) Thousands more children and young people in Greater Manchester get the help they need thanks to improved mental health services. Thousands more children and young people in Greater Manchester get the help they need thanks to improvements to mental health services - GMHSC. Accessed 01/11/2022.

- GMCA (2022) Young People to design new mental health initiative in Greater Manchester Schools. Young People to design new mental health initiative in Greater Manchester high schools - GMHSC. Accessed 01/11/2022.

- Kousoulis et al (2021) Promoting and Protecting Mental Health: A Delphi Consensus Study for Actionable Public Mental Health Messages. N.B. Access to this paper is behind a paywall. The Mental Health Foundation reported the findings on their website in October 2021: Groundbreaking study combines expert views, research evidence and public opinion to generate new mental health advice | Mental Health Foundation

- Marquez et al (2022) Loneliness in young people - a multilevel exploration of social ecological influences and geographic variation

- Mendolia et al (2022) Have girls been left behind during COVID-19 – gender differences in pandemic effects on mental wellbeing

- Mental Health Foundation (2022) Our Best Mental Health Tips Backed by Research

- Mind (2018) Sport and physical activity for people with mental health problems: a toolkit for the sports sector

- Mind (2021) Coronavirus: The consequences for mental health. The ongoing impact of the coronavirus pandemic on people with mental health problems across England and Wales

- MIND (2021) Not making the grade: why our approach to mental health at secondary school is failing young people

- National MWIA Collaborative (2011) Mental Wellbeing Impact Assessment - A toolkit for wellbeing

- New Economics Foundation (2011) Five Ways to Wellbeing: New applications, new ways of thinking

- NHS Digital (2021) Mental Health of Children and Young People 2021

- NICE (2022) Mental Health and the NHS: What’s changed and what’s to come? Mental health and the NHS (nice.org.uk) Accessed 31/10/2022.

- Radez, Reardon et al (2021) Why do adolescents not seek and access professional help for their mental health problems? A systematic review of quantitative and qualitative studies

- Sport for Development Coalition (2022) Moving for Mental Health Policy Brief

- Sport for Development Coalition (2022) Moving for Mental Health Research Report

- Sported (2022) Time in Mind: Learning from practices in mental health support for young people in community sports groups

- Student Minds (2022) Student Mental Health: Life in a Pandemic – Wave 3 findings

- The Children’s Society (2022) The Good Childhood Report

- Women in Sport (2022) Reframing Sport for Teenage Girls – Tackling Teenage Disengagement

- World Health Organization (2022) Physical Activity Fact Sheet. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/physical-activity. Accessed 01/11/2022.

- Wu et al (2017) Top-down or button-up? The reciprocal longitudinal relationship between athletes’ team satisfaction and life satisfaction

- Youth Sport Trust (2022) PE & School Sport Survey